Thomas Merton was a Trappist monk of one of the most rigorous orders which he entered in his twenties after quite a wild youth. Merton sought and wrote so lucidly about cultivating a spiritual practice in modern life, that he has been likened to a zen monk in his simplicity, commitment and the breadth of his wisdom.

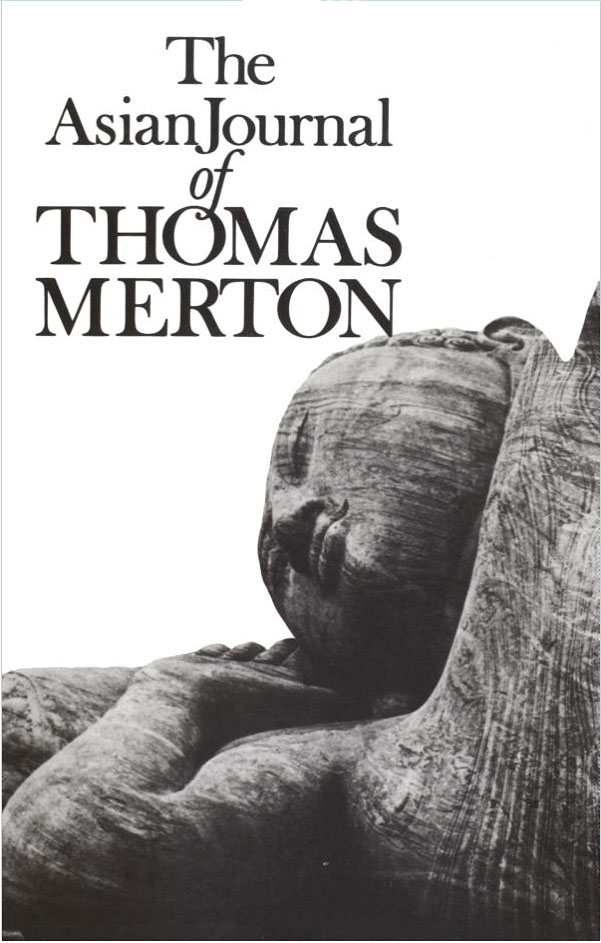

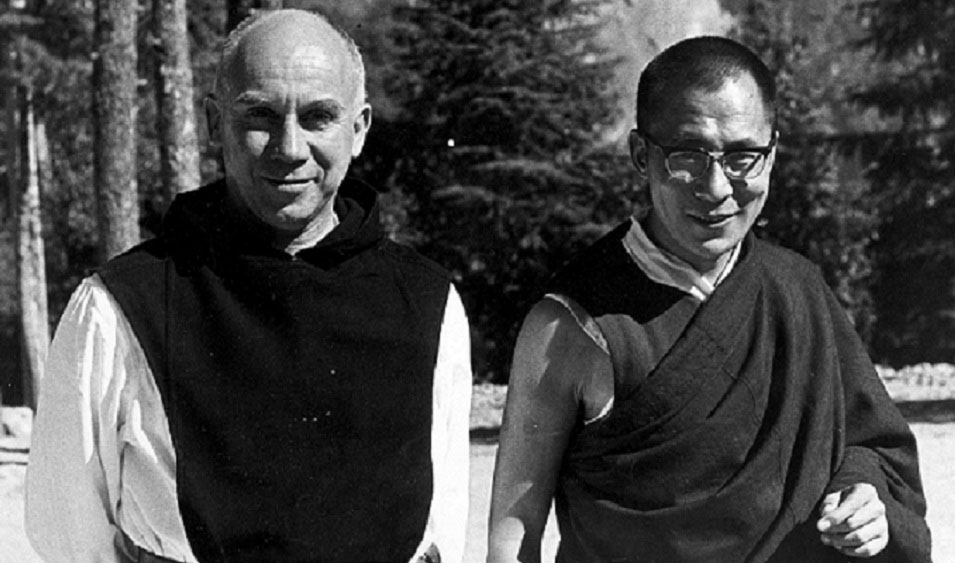

We found Merton when we were in our late twenties, searching for anyone who could help guide our path. Though we are not Catholic, his writings resonated mightily, particularly The Asian Journal, written near the end of his life during his much-longed for journey to Asia, where he met with practitioners of many Eastern traditions, including the Dalai Lama. For us, his greatest lesson was that it is each person’s calling to “be truly and authentically herself”.

He wrote:

“…I stand among you as one who offers a small message of hope, that first, there are always people who dare to seek on the margin of society, who are not dependent on social acceptance, not dependent on social routine, and prefer a kind of free-floating existence under a state of risk. And among these people, if they are faithful to their own calling, to their own vocation, and to their own message from God, communication on the deepest level is possible. And the deepest level of communication is not communication, but communion. It is wordless. It is beyond words, and it is beyond speech and beyond concept.”

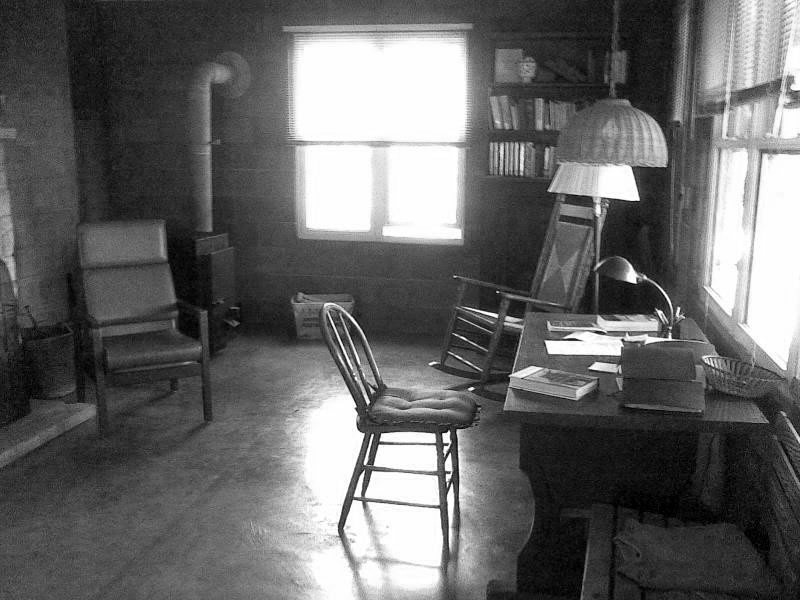

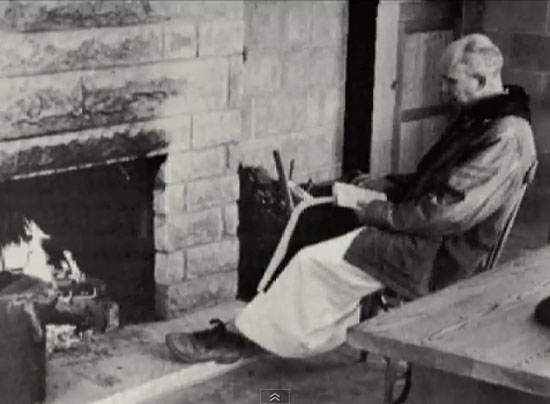

We admired Merton’s desire to live in solitude, in a hermitage at Gethsemeni where he wrote his many books and kept a vast correspondence.

An outsider in his own world, he understood that the real work was the process, not apparent success:

“…do not depend on the hope of results. …you may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.”

Parker J. Palmer, founder of the Center for Courage & Renewal, describes the way the “notion of paradox was central to Merton’s spiritual and intellectual life, not merely as a philosophical concept but as a lived reality” and a key to a truly creative life:

Merton taught me the importance of looking at life not merely in terms of either-or but also in terms of both-and. Paradoxical thinking of this sort is key to creativity, which comes from the capacity to entertain apparently contradictory ideas in a way that stretches the mind and opens the heart to something new. Paradox is also a way of being that’s key to wholeness, which does not mean perfection: it means embracing brokenness as an integral part of life.

For me, the ability to hold life paradoxically became a life-saver. Among other things, it helped me integrate three devastating experiences of clinical depression, which were as dark for me as it must have been for Jonas inside the belly of that whale. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” was the question that came time and again as my quest for light plunged me into darkness. In response, Merton’s lived understanding of paradox came to my rescue. Eventually I was able to see that the closer I move to the source of light, the deeper my shadow becomes. To be whole I have to be able to say I am both shadow and light.

This trailer of a film about Merton gives a sense of his complexity and struggle; he was no ordinary Catholic monk. (Video link HERE.)

We managed to find our favorite passage of The Asian Journal, written only a few days before Merton died, after seeing the Reclining Buddha in Polonnaruwa in Ceylon:

Hello, Sally,

I have been a member with benefits since last spring and continue to have issues – I invariably get a message that I have used up my article allotment and then when I complete the tinypass sign -in there is no direct way back to the article – you cannot exit the tinypass sign in page – there is no way to close it and go back to Improvised Life. I don’t think you have a good interface for mobile phones. I only read you from my phone. Please help as I love the site but it is quite frustrating. I have a Windows phone.

,

Thanks so much,

Susan

Hi, I’m so sorry to hear you’re having trouble with Tinypass.

I’ve been trying to duplicate your problem. When I get the paywall and signin, I get an acknowlegement and a link to go back to reading; it takes me to the page I was on.

Unless you have set your phone not to store site info, you shouldn’t have to sign in more than occasionally.

If possible, please send more specific info and I will try to figure out what’s going on.

—What kind of phone are you using?

—What OS?

—Can you take a screen shot of the window you get after signing in? That would be the biggest help.

—And I’d love some specifics as to what you don’t like about the phone reading experience, with screenshots if possible. Perhaps the site is reading differently on your device. (When implementing the design, we try to make it work for as many devices as possible, but it can take some fine tuning).

I am sure that with this info we can get things working better for you.

These pics are amazing. i will share them on my blog here:http://filmhastasi.blog.com/